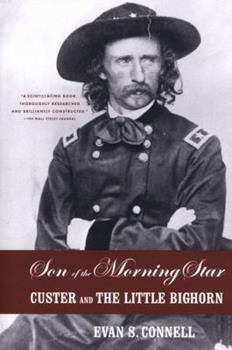

Son of the Morning Star

September 20, 2022

Son of the Morning Star

by Evan S. Connell

Like Boone, this book was recommended by Steven Rinella on the Tim Ferris podcast. I decided to read it this year to learn more about Custer, since we were taking a family vacation to Yellowstone that would pass through the part of the country where he died.

When Connell was researching this book, he drove many times to the battlefield where Custer’s Last Stand occurred. Each time, we chose a different route, and he hit every library along the way to see what Custer-related books they had that he hadn’t already read. That’s basically how he did his research.

The book, published in 1984, assumes you know the basic facts, which I did not. So I learned about them piecemeal throughout. The structure is idiosyncratic and jumps around a bit in time, but the book is packed with interesting details. Here are some in no particular order. There are large chunks of the book that I did not take notes on, since I was mainly trying (and failing) to complete the audio before our trip.

Canada had many of the same Indian tribes and same “greedy, dominant Anglo-Saxon race” (12), but they avoided war and massacres. There’s no single reason for this, but a big one is that the Canadian government kept their word to the Indians. In America, at the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), America established a Souix reservation and granted them ownership of the Black Hills (modern South Dakota). But prospectors found gold in the Black Hills, and in 1874 the US sent Custer on an expedition to the area, partly to confirm whether there was gold in them there hills. The government broke their treaty in order to go after the gold. (82)

Captain Fred Benteen looked like a child with “feminine lips” (30), had his Confederate father arrested to keep him safe (31-32), lost 4 of his 5 children to menengitis, and was a heavy drinker. He once wrote:

I've been a loser in a way, all my life by rubbing a bit against the angles--or hairs--of folks, instead of going with their whims; but I couldn't do otherwise--'twould be against the grain of myself.

He was “the only man [Lt. Varnum] ever saw who did not try to dodge bullets.” (53)

Major Reno was the real loser. He set the West Point record for demerits, with over 1000. From the day he entered West Point, “he radiated an aura of misfortune.” (41) His wife died unexpectedly (42), and he was denied permission to attend her funeral! She came from a wealthy family, but they despised him and made sure he didn’t get a dime from them.

He was almost dismissed from the army for making passes at Capt. Bell’s wife (44), but President Hayes reduced his punishment to two years’ suspension without pay. Once restored to active duty, he “felt himself overcome with passion for Col. Sturgis’ daughter” Ella, who was 22. Reno was now a “paunchy, middle-aged alcoholic.” Reno was caught peeking in on her from the bushes. He was dishonorably discharged, (46) although after his death this was repealed (48).

He tried to sell his battlefield diary to a newspaper in New York, but they rejected it. He eventually died of tongue cancer in 1889.

His best contribution to the battle may have been his cowardice. As someone commented during an inquiry years later, “If we had not been commanded by a coward we would all have been killed.” (49)

(All this about Reno is told on pages 40-49, and much of it happens after the famous battle at the Little Bighorn.)

The Indians apparently used bows and arrows against Custer, then picked up their carbines and used those against Benteen (53).

Some Sioux amputated a finger with a dull knife when mourning (54). It would leave exposed bone after healing.

How small incidents were handled could have big consequences. In 1854, an Indian named High Forehead shot a Mormon’s cow that wondered too close to the Sioux camp. So an army inspector, Grattan, concluded, “It’s time to put these Indians in their place.” Thus began “a generation of savagery.” (67)

When Crazy Horse dressed for battle, “he painted white hail spots on his body and a red lightning bolt down one cheek… He tied a brown pebble behind one ear, wore the red-backed hawk on his head, and threw a handful of dust–perhaps symbolic of the storm–across himself and his pony. Except for moccasins and breechcloth he rode naked.” (67)

Like Custer before his last stand, Crazy Horse was never wounded in battle, though a number of horses were killed beneath him. (68)

There was a period when Crazy Horse was a serial killer. He killed miners panning for gold in the Black Hills and drove an arrow into the ground next to each corpse, like a calling card. (70) He “grew more strange” over time. “There are no authenticated photos of him.,” (72) because he “did not want to lose himself inside the white man’s box.”

He was arrested by Crook in 1877, and bayoneted and killed during the arrest. He would have been imprisoned in Dry Tortugas, Florida. (73-74)

Page 75 describes the “Crazy Horse cult.” He epitomized the Indian as we see them – gnomic, a genius in war, a lover of peace, a legend. God used Crazy Horse to achieve His purposes, but from the pagan perspective, it seems random and pointless. “One is inclined to ask, what is it all about?” (75)

Sheridan’s plan to chastise the warlike tribes involved three armies converging on the savages. Gen. George Crook would move north from Ft. Fetterman (in WY), Col. John Gibbon would move east from MT, and Gen. Alfred Terry (with Custer commanding the Seventh Cavalry) would move west from the Dakota Territory. (83)

Crook was an experienced Indian fighter, a mean opponent, “worse than a badger in a barrel.” (83)

People thought the Sioux were cannibals, and this may have started because of some Sioux playing a joke on a Cheyenne (84). The Cheyenne came up to them, didn’t know their language, and helped himself to a piece of their meat. When he had eaten some, they signed to him that they’d cut up a fat soldier and cooked him. They looked serious, and he was horrified; it was a joke, but word got back to the white man.

The origins and etymologies of various tribal names are given on page 86ff. Unkpapa means edge/border, where this tribe would camp. “They Camp by Themselves.” Miniconjoux means they plant crops beside water. Oglala means “divided.” Some odd stories, like this:

Those without bows, Sans Arcs, got this name after some family or clan found itself disarmed--which was the fault of an hermaphrodite... [Hermaphrodites] lived out their existence amont the Indians in terrible isolation. The year 1839 is recorded on an Unkpapa pictographic calendar as Winkte Peji wan ici kte, "the year an hermaphrodite commited suicide." Nevertheless they had a certain status not granted them in Anglo-Saxon society; they were thought to possess great powers of divination and therefore would be consulted on important business. (87)

One time an hermaphrodite told the tribe to leave their weapons on a certain hill-top, and while they were unarmed, a war party came along and massacred them.

Like scenes from McMurtry, you get a sense of the savage Indian way of life from some of these stories:

[Some Crows] heard a voice begging for water, "Mini! Mini!" and they discovered a blind Cheyenne warrior hidden among the rocks... When he heard the Crows talking among themselves he mistook their language for Sioux and called out. The Crows responded by chopping off his arms and legs. (90)

But there are other cases where the scenes are not like McMurtry. A woman named Mrs. Kelly was captured by Indians, and:

She was not sexually abused. Not by Oglalas, Unkpapas, or Blackfeet. They ordered her about with harshness and cruelty, "yet I had never suffered from any of them the slightest personal or unchaste insult." (97)

*** There’s a long story on pp. 90-92 about Brt. Col. Guy Henry. He was shot in the head but stayed upright in the saddle and continued to encourage his troops. When someone commented later, he said, “It’s nothing. For this we are soldiers.” People were sure he would die that night. “The doctors have told me that I must die,” he said, “but I will not.” Trying to carry him on a litter hooked up to a mule, they dumped him down a mountainside – he fell 20 feet onto some rocks. When they brought him water and asked how he felt, he whispered, “Bully!” and thanked them for their kindness. At one point, the mule kicked him in the face. As the company retreated, “nights were so cold that ice formed. He welcomed the low temperature because he did not bleed as much.” He was nearly washed overboard while crossing a river.

Eventually, they make it to a fort, and he is loaded on a train. “At Fort Russell the surgeons went to work, probing his wounds every day, but even they could not kill him.” He spent a year recovering and then returned to duty at Fort Laramie! As for Henry, he saw nothing special about this experience. He was a warrior and kept his feelings to himself.

“As values change, so does one’s evaluation of the past and one’s impressions of long gone actors. New myths replace the old. During the 19th century, GAC was vastly admired. Today his image has fallen face down in mud.” (106) His image “was gradually altered into a symbol of the arrogance and brutality displayed in white exploitation” (contrary to historical fact, he says).

Custer “never prayed as others do,” but always did pray before battle, commending himself to God’s care and asking Him to forgive his sins. (112)

He gave up drinking (114) after an incident with his sister Lydia. “At the same time he renounced profanity, but here he was less successfuly.” His wife Elizabeth Bacon Custer laughed at him for brushing his teeth after every meal and for how frequently he washed his hands. (116)

Whenever he met an enemy, Custer attacked like a beserker. He gave the impression of a preposterous, comic figure, “which he was and was not. Behind the pranks and the outrageous costume rode a killer.” (117)

Custer was present at Appomattox. There Sheridan bought the pine table where Grant accepted Lee’s surrender. He gave it to Custer as a gift for Elizabeth. “Custer rode away with this important table balanced upside-down on his head.” (119)

In October 1865, Custer and Elizabeth visited the Texas State School for the Deaf. (It’s still there! CHS played them in softball in 2022.) Custer was impressed by how the deaf communicated. Later, he would be pretty good at communicating non-verbally with Indians, and he may have learned some of this skill there.

“On Christmas Day, 1865, he wore a Santa Claus suit while distributing gifts to members of his staff.” (123)

Regarding race,

He held a visceral conviction that as a race the white race was what mattered: "I am in favor of elevating the negro to the extent of his capacity and intelligence, and of our doing everything in our power to advance the race morally and mentally as well as physically, also socially. But I am opposed to making this advance by correspondingly debasing any portion of the white race. As to trusting the negro of the Southern States with the most sacred and responsible privilege--the right of suffrage--I should as soon think of elevating an Indian Chief to the Popedom of Rome." (125)

He was known to sleep with his black cook. This was considered to be in bad taste by his soldiers, not because of the adultery but because of her looks!

For some reason, Indians did not like to fight black soldiers and never scalped them. “Buffalo soldier no good, heap bad medicine.” (126)

“McKenny had less influence than a chipmunk in a forest fire.” (127 – Connell is pretty funny sometimes)

In his book Custer reproduced a telegram from Sherman to Grant, dated one week after the slaughter, which says in part: "We must act with vindietive earnestness against the Sioux, even totheir extermination, men, women, and children. Nothing less will reach the root of the case." If one word of this extraordinary telegram is altered it reads like a message from Eichmann to Hitler. (132)

Opinions vary re: whether the Indians were conservationists or profligate wasters. See pp. 137-8.

On page 218, Sitting Bull is given a demonstration of the telephone. “These were men who had endured the torture of the Sun Dance and had been ready to give their lives at the Little Bighorn, but after this horrifying experience they became urgent advocates of peace.”

Human hair then possessed a cultural significance which it lacks today. Miniature pictures were created by combining various textures and colors. Men wore watch chains of braided hair. Women exchanged gifts made of hair. Two of Elizabeth's presents on her thirteenth birthday were a bracelet of her mother's hair with her father's hair in the clasp, and some of her aunt's hair braided into the shape of a heart. On December 23, 1863, she wrote to her new husband: "Old fellow with the golden curls, save them from the barber's. When I'm old I'll have a wig made from them." So he did, and she did--although she did not wait until she was old. She wore this wig at least once to a Fort Lincoln dress ball and she probably wore it several times during amateur theatricals. (345)