Lincoln's Melancholy

November 17, 2021

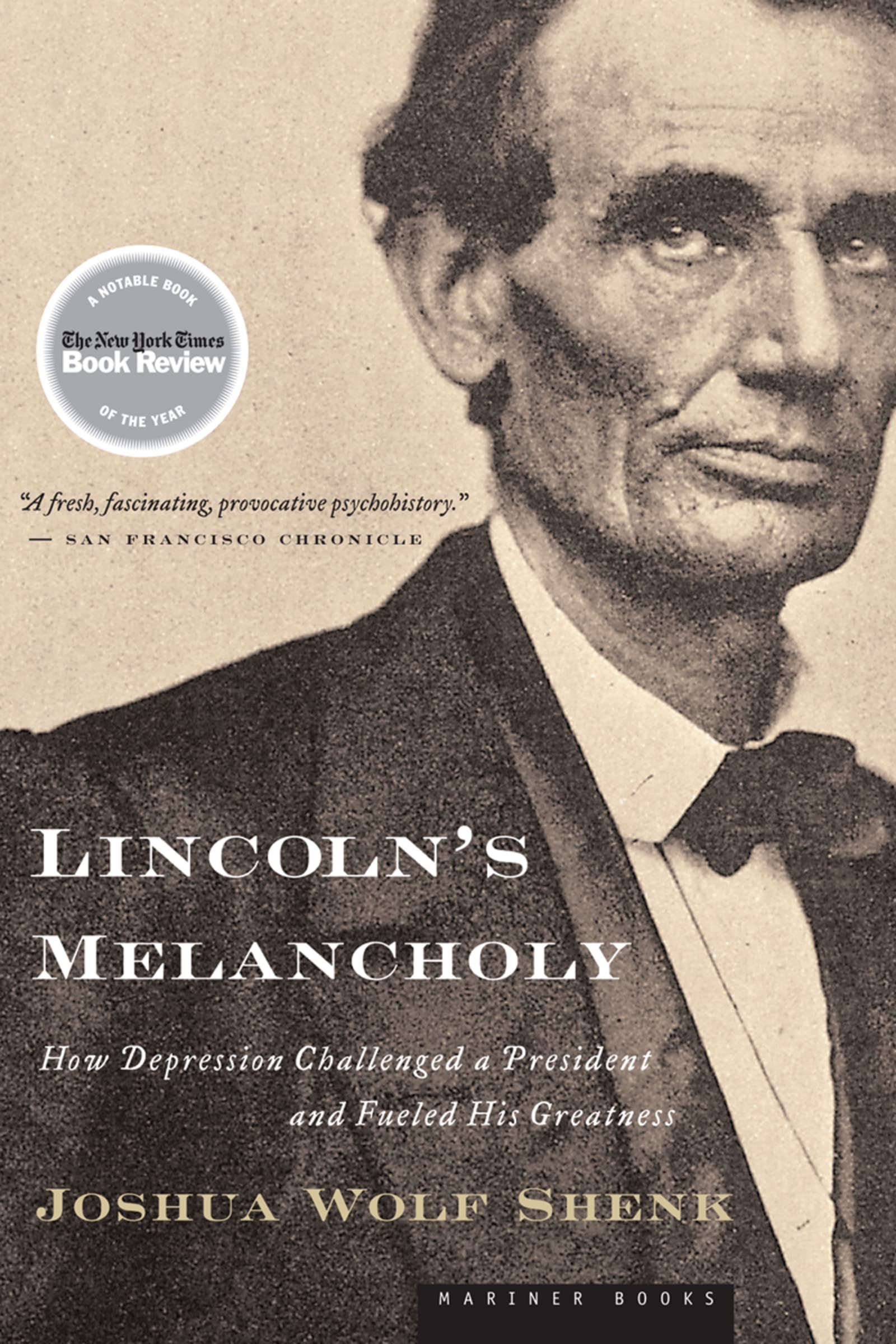

Lincoln's Melancholy

by Joshua Wolf Shenk

Pastor recommended this, and I wanted to read it before reading Lincoln in the Bardo.

Intro

He often wept in public and recited maudlin poetry. He told jokes and stories at odd times – he needed the laughs, he said, for his survival. As a young man he talked of suicide, and as he grew older, he said he saw the world as hard and grim, full of misery, made that way by fates and forces of God. (4)

Chapter 1

In Boone, I learned that Daniel Boone led Captain Abraham Lincoln (AL’s grandfather) over the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky in 1779. AL was born in Kentucky on Feb 12, 1809. His younger brother, Thomas, died in infancy. His mother Nancy died when he was nine (in 1818) after drinking milk from a cow that had eaten a poisonous root. His older sister, Sarah, died in childbirth at the age of 19.

Lincoln loved to read, which his father stopped encouraging when it began interfering with farm work. His self-education continued in defiance of both his father and societal norms. In his teens and twenties, Lincoln seemed “sunny and indefatigable,” good natured, social. He had the ambition to become a lawyer, the pluck to do it basically on his own through reading, and a sense of calling.

At age 26, he had his first major depressive episode, after the death of Ann Rutledge, triggered also by the winter weather. It was bad. Those around him were on suicide watch. He wandered around in the woods with a gun. Later, he chose never to carry a pocket knife, fearing he might harm himself in a bout of depression.

Chapter 2

In Lincoln’s time, melancholy was intriguing. “Gloom was a unique experience” characterized by “deep reflection, perseverance, and great energy of action.” (30) Lord Byron wrote, “Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most / Must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth.” He called melancholy “the telescope of truth.” Melancholy was also called “the hypo” (for “hypochondriasis”; see the opening passage of Moby-Dick). Dour moods can lead to adventure.

Joshua Speed said Lincoln was guileless, perfectly natural.

Chapter 3

As a member of the state legislature of Illinois, he conspired with other Whigs to prevent a quorum on a certain vote. When it turned out that the exact number for a quorum was present, he “very unceremoniously raised the window and jumped out.” (Therefore, I think he should be known as “The Great Defenestrator.”)

Hypochondriasis = “a disease of the organs below,” coming from hypo (below) and khondros (the cartilage of the rib cage). (58) Originally meant “depression without reason” (so you can see the connection to the modern term, hypochondriac).

Horrible treatments were applied, like bleeding the patient, blistering him with heated glass cups, and giving drugs to induce diarrhea and vomiting. Mustard rubs, black pepper drinks, mercury, arsenic, and strychnine!

The winter of 1840-41 was a low point for Lincoln. He was roommates with Joshua Speed above a store in Springfield, but that was ending (Speed no longer worked at the store as of Jan. 1). There were issues with the state debt, and Lincoln was responsible for some of the trouble. Speed intended to propose to a woman AL was interested in. AL had proposed to another woman and been rejected. And he may (it’s speculated) have been suffering from a venereal disease. (55-56)

He wrote, “I am the most miserable man living.” He told Speed that he was not afraid to die, and thought seriously of killing himself. Yet “he had an irrepressible desire to accomplish something while he lived. He wanted to connect his name with the great events of his generation.” (65)

Chapter 4

A new culture arose in America “centered on the independent self.” While today we take the “self” for granted and struggle to connect to something larger, being self-oriented was a new idea at this time (see Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”… but don’t). Inner life, personal ambition, and self-improvement were emerging in the national character. Young men were encouranged to “push hard.” “Who succeeds? Who makes money, honor, and reputation [Note what is considered success]? He who heartily, sincerely, manfully pushed, and he only.” (73)

These admonitions were written to young men whose fathers were farmers or tradesmen, content with a hard day’s work providing for their family and keeping them safe. The new national spirit was of discontent, striving. It is the spirit of man, of Babel, of the modern age.

When Thoreau wrote that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation,” “he was quarreling with an emerging culture that scorned a man who did odd jobs, lived on a pond, and wrote poetry for no money.” At his funeral, Emerson considered it a fault that Thoreau “had no ambition.” (75)

Chapter 5

Lincoln’s parents belonged to “a fire-breathing sect called Separate Baptism” that involved a lot of hellfire preaching. Lincoln became an apostate. “He left the Baptist church… He became widely known as an infidel. He rejected eternal damnation, innate sin, the divinity of Jesus, and the infallibility of the Bible.” (82) He never joined a church.

Following the spirit of the age, of self reliance, “many freethinkers constructed a faith in their own minds,” rejecting orthodoxy. Contrast this with Christians who “take every thought captive to Christ” (2 Cor. 10:5). The book includes Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson among the ranks of freethinkers (all Freemasons, too). Thomas Paine’s argument for deism (and for rejecting the Bible) is titled “The Age of Reason.” If reason/rationality is your god, then like Emerson you place yourself as the judge and arbiter of truth and morality, which sounds a lot like Lucifer telling Eve, “You will be like God, knowing good from evil.”

Lincoln also “subscribed to a school of thought known as fatalism” (90), believing destinies “had been laid out in advance” (by Whom?). I find this at odds with the spirit of striving; if your fate is sealed and your actions are foreordained, why strive? But I suppose a fatalist must answer that they have to choice in this either.

Speed said, “In early life… he had tried hard to be a believer, but his reason could not grasp and solve the great problem of redemption as taught.” (195) He visited church (“rented a pew” ??? at First Presbyterian, page 196), but that’s all. He maintained “that God could not forgive; that punishment has to follow sin.”

Yet he expresses the Divine will – see “Meditation on the Divine Will” (196) – rather well.

Chapter 6

Chronic depressives often choose professions that serve and suffer on behalf of others. (103)

When performing work you do well, you tend to do it with more enjoyment and less fatigue. For work you don’t do well, you tend to look at it in disgust, turn from it, and imagine yourself exceedingly tired. (103)

His father Tom was sick, and Lincoln sent a message but did not go visit him. When Tom died, Lincoln did not attend his funeral. (107)

Chapter 7

“Laughter practically disappears in isolation.” (How rarely do you laugh out loud when reading alone! It’s wonderful but very rare even for me, and I laugh easily.)

Lincoln vented his melancholy through humor. “His well of stories never ran dry because he was always refilling it.” (115) I laughed at this one:

Once he told a story about an extremely ugly man walking on a narrow road. A woman came by and examined him closely. "You," she said, "are the ugliest man I ever saw." Sadly, the man answered, "Perhaps so, but I can't help that." "No," the woman allowed, "but you might stay at home."

There is a lawyer friend of Lincoln’s named Orlando B. Ficklin. What a great name! Ficklin could see the contrast between his humor and gloom. He said, “It’s not that his moods turned in a cycle, as day gives way to night, but that he lived in the night and made a strong effort to bring the sun in.” (117)

His humorous side was well-known, as shown in this funny story (page 182) of two old ladies talking about the war: One said, “I think Jefferson Davis will succeed because he is a praying man.” The other replied, “But so is Lincoln.” “Yes, but when Abraham prays, the Lord will think he’s joking.”

Chapter 8

Victor Frankl: “What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for a worthwhile goal.” (126) Lincoln’s worthwhile goal became the ending of slavery.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act, explained on 130, is important. Championed by Stephen Douglas, it would repeal the Missouri Compromise and allow new stated to simply vote on whether they would be slave or free states. Douglas made a deal with some southern senators (140), who would vote for the KS-NE Act if the MO Compromise was first repealed.

Now we call opposition to slavery “abolitionism,” but that term meant a radical opposition that sought to bring down the government over this issue. “It is tempting to imagine that northerners harbored animosity toward slavery and sympathy for the enslaved,” but Illinois barred free black people from entering the state at all. (131)

Lincoln’s strength was in persuading others to change their minds. “His listeners felt that he believed every word he said, and that, like Martin Luther, he would go to the stake rather than abate one jot or tittle of it.” (132)

“It is common sense that some situations call for pessimism, but as a culture Americans have strongly decided to endow optimism with unqualified favor.” (134) Pessimism or melancholy today would look like a defect. Psychologists see it as a brain disease. “Therapy and medication can help you see the world the way healthy optimists do.” (134) Consulting a psychiatrist or therapist is now “an unforgiveable sin for an American politician.” (166) “Somehow, anything short of constant cheer has come to be perceived as a violation of the American religion.” (167)

“If most of us remain ignorant of ourselves, it is because self-knowledge is painful and we prefer the pleasures of illusion.” –Aldous Huxley (136)

“Melancholic success” is widely acknowledged but poorly understood. Melancholics tend to have low energy but to use that energy well. The “work hard…, do great things, and derive little pleasure from their accomplishments.” (136)

Lincoln believed that the Founders understood that slavery was a national evil, and they deliberately hid the resolution to it in the Constitution, believing that they could not eradicate it in their own lifetimes while preserving liberty. (137) He said, “The assertion that ‘all men are created equal’ was of no practical use in effecting our separation from Great Britain, and it was placed in the Declaration, not for that, but for future use.” (138)

Adopting a “widely shared white fantasy,” he expected that black people would migrate to Africa or other foreign lands after receiving their legal freedom. (139) He was “not in favor of … social and political equality of the white and black races” (153).

Lincoln did not expect quick results. “Whoever heard of a reformer reaping the reward of his labors in his lifetime?” (151)

Lincoln’s melancholy doesn’t lend itself to a “crisis and recovery” narrative. It wasn’t something he had to overcome. The problem of his melancholy was fuel for the fire of his great work. (156)

Chapter 9

On page 162 there is an account of a speech he gave in NYC on whether the founders supported federal regulation of slavery. They expected the ravings of a bumpkin, and he provided a thorough and cogent case that the founders did support such regulation.

What distinguishes creative people? Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (“Me-high Cheek-sent-me-high”) sums it up as: “Complexity.” They “show tendencies of thought and action that in most people are segragated.” (See the Fitzgerald quote in the bio of Boone about holding “two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time”.) He observed that creators were “both wild and subdued, rebellious and pragmatic, cooperative and aggressive.” (165) Unrelated, but Csikszentmihalyi coined the term “flow,” as in the flow state, and he’s known as “the godfather of flow,” which I think makes him sound like a rapper.

“The idea of the tortured genius is simplistic, insofar as it suggests that being tortured, by itself, is worth anything.” (165)

The Civil War began barely 3 months after Lincoln was elected (Feb 18, 1861).

A wonderful example of editing a speech is given on page 174. Seward wrote a draft which AL edited, and we have the before and after, so we can see what he changed. It is the “better angels of our nature” speech, and the edits highlight his rhetorical skill and what he wished to convey.

His son Willie, age eleven, died from an illness on Feb 20, 1862, almost exactly a year into the war.

Psychiatrist George Vaillant lists five ways healthy people deal with problems, all of which Lincoln exhibits. Humor (to engage with reality while enjoying its absurdities), suppression (but not denial), anticipation (looking ahead to both good and bad that lie in the future), altruism (looking after the welfare of others), and sublimation (channeling passions into art). (183)

Chapter 10

The author’s summary of Job on p. 200 is so wrong that it makes me doubt the rest of the book.

Democratic general George McClellan “supported the war but opposed emancipation.” If that’s true, what did he consider the purpose of the war to be?

Lincoln was shot on Good Friday (4/14/1865). He died the next morning.

Epilogue

About the depressive, one might say, “He can’t help it. He has an illness and should be treated with deference.” Another might shake his head and say, “He needs a swift kick in the butt.” Lincoln shows that both viewpoints can be true. His time of mental agony was also a time of gestation and growth; the swift kick in the butt would not help this. But he also could not be left to wallow; it was vital that he rouse himself when the time came. (214)