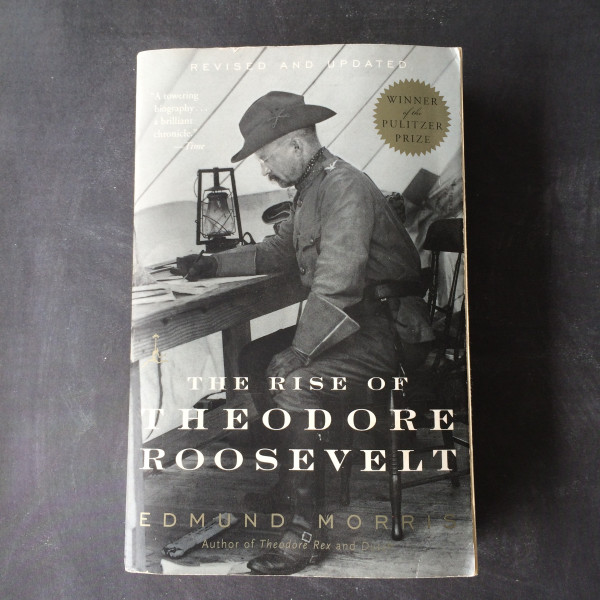

The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt

October 14, 2019

The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt

by Edmund Morris

[I finished this book in October 2019, but I did not finish writing up these notes until January 2020! It was a mistake not to keep the notes as I went along, since there is so much that I wanted to remember. I also began the notes in a single long entry but later (at ch. 11) began organizing them by chapter, which is better. I will not go back and update the early notes to match this, though. The notes are for myself, and I don’t mind their idiosyncracies.]

Oct. 27, 1858 - born in NYC to Theodore Sr. and Martha (Mittie). He suffered from asthma, and his father cared for him with great compassion. TR Sr.’s “charity extended as far as sick kittens, which could be seen peeking form his pockets as he drove down Broadway.” (p. 4)

Mittie was a Southerner and sided with the Confederacy, in conflict with her husband. Her mother (Grandmother Bulloch) and sister (Annie) lived with them in New York. Their family owned slaves and a plantation (p. 9). Once, after a Southern victory, Mittie hung the confederate flag (“the Stars and Bars”) up at their house.

TR Sr. did not feel he could join the Union army, since it could mean firing upon his own Southern brothers-in-law, so he hired a substitute soldier. Being unable to fight, he instead worked for the soldiers politically. The soldiers were spending all their military pay on food and liquor sold in the camps by “sutlers,” who charged such high prices that the soldiers had no money to send home. TR Sr. worked to get Allotment Commissioners assigned to the camps to persuade the soldiers to voluntarily set aside money to support their families. “For three months they worked in Washington to secure the passage of this act – delayed by the utter inability of Congress to understand why anyone should urge a bill from which no one could selfishly secure an advantage.” (p. 9)

Interest in nature and wildlife

At age 7, TR procured the skull of a seal from a market on Broadway. He and two cousins started the “Roosevelt Museum of Natural History,” featuring that skull, and he began writing observations about insects and other wildlife. His interest “became something of a trial to his elders. Meeting Mrs. Hamilton Fish on a streetcar, he absentmindedly lifted his hat, whereupon several frogs leaped out of it, to the dismay of fellow passengers.” (p. 19)

From time to time, members of the domestic staff threatened to give notice. A protest by a chambermaid forced Teedie to move the Roosevelt Museum of Natural History out of his bedroom and insto the back hall upstairs. "How can I do laundry," complained the washerwoman, "with a snapping turtle tied to the leg of the sink?"

1869 - family trip across Europe

AKA “the Roosevelt Grand Tour.” They were away from home 377 days. He was 10 at the start of the trip and mentions crying when leaving a friend, 7 year old Edith Carrow, who he would later marry. (p. 22) He fed Italian beggars “like chickens” (p. 27) and met the pope (p. 29), kissing his hand even though he wasn’t Catholic.

Making his body

When TR was around 12-13, his dad told him (p. 32), “You have the mind but you have not the body, and without the help of the body the mind cannot go as far as it should. You must make your body, It is hard drudgery to make one’s body, but I know you will do it.” He began daily exercise, and mention of illness disappears from his diary for quite a stretch. Previously, he’d had regular trouble with asthma and diarrhea, which he and his family euphamistically called cholera morbus.

1876 - TR goes to Harvard

He is hardly recognizeable in the picture of him as a freshman (p. 55). He looks rather tough!

I love the description of club life on campus. A bunch of ridiculously named groups like the Hasty Pudding Club give each other a hard time via essays, poems, and public speeches. This is where the upper crust socialized. “Showing the self-protective instinct of a born snob, he carefully researched the ‘antecedants’ of personal friends.” (p. 58) He had a “scout” (servant) to “make the fire and black the boots” (p. 61).

He was “rigidly virtuous” and considered sex “part of the mystical union of marriage.” (p. 63) He and Edith had “an understanding,” and he was faithful to her. He became a real dandy, dressing very fashionably.

In July 1877, he published his first book: The Summer Birds of the Adirondacks. It was well reviewed and probably convinced his father that he would do well with a career in the sciences. Page 67:

My father... explained that I must be sure that I really intensely desired to do scientific work, because if I went into it I must make it a serious career; [he could afford to pay for it,] if I intended to do the very best work that was in me; but that I must not dream of taking it up as a dilettant. ... [also:] If I was not going to earn money, I must even things up by not spending it.

His father died the next February, 1878.

He met Alice Lee that November and resolved to marry her (Alas! Edith!). They began to see each other more. He got into boxing (memorable moments ~p. 90). He successfully proposed, got her father’s consent (for not just an early engagement but an early marriage), and married Alice on Oct. 27, 1880, his 22nd birthday.

Nov. 1880 - starts at Columbia Law School

He argued with the professor, arguing “for justice and against legalism,” expressing “contempt for the ‘repellant’ doctrine of caveat emptor.” After classes, he worked on his book, The Naval War of 1812. The book came out in 1882. It “was the first and in some ways the most enduring of TR’s 38 books.” It became a college textbook, was ordered placed on every US Navy vessel in 1886, and remained the definitive work on that subject for a century. Not bad for a twenty-three year old author.

NY State Assembly

He also began spending time at Morton Hall (p. 125), Republican headquarters for the district. He was nominated to the New York State Assembly and won in Nov. 1881. When he showed up,

His hair was parted in the center, and he had sideburns. He wore a single eye-glass, with a gold chain over his ear. He had on a cutaway coat with one button at the top, and the ends of its tails almost reached the tops of his shoes. He carried a gold-headed cane in one hand, a silk hat in the other, and he walked in the bent-over fashion that was the style with the young men of the day. His trousers were as tight as a tailer could make them, and he had a ball-shaped bottom to cover his shoes.

"Who's the dude?" I [John Walsh] asked another member.

The other assemblymen made fun of him and thought he was ridiculous at first. But TR made trouble, boldly calling (on p. 157) for investigation into some seedy graft that was going on with a certain judge. The details aren’t that important, only that he stuck to his guns and was so full of life and liveliness that he steamrolled less vivacious opponents.

He was named speaker of the assembly in 1883. In a speech, he coined the term “the wealthy criminal class” for railroad-baron types.

The Badlands - 1883

Alice was now pregnant, and he was planning a home for them called Leeholm, to be built on a hill in Oyster Bay.

At a party in May, 1883 (p. 182), he met Commander Gorringe, who invited him to come on a buffalo hunting trip in the Badlands of the Dakota Territory. He agreed, and left NY by train in September. The Sioux and the government had killed thousands of buffalo in the area since May, including ten thousand killed a week before TR arrived there, so the pickin’s were slim.

History writing is often considered dry, but this book beautifully written. Check out this description of the Badlands from p. 198:

It was [General Alfred Sully] who coined the classic description of the Badlands: "hell with the fires out." Seen by Roosevelt in the gloom of early evening, it must indeed have seemed like a landscape of death. There were pillars of corpse-blue clay, carved by wind and water into threatening shapes; spectral groves where mist curled around the roots of naked trees; logs of what looked like red, rotting cedar, but which to the touch felt petrified, cold, and hard as marble; drifts of sterile sand, littered with buffalo skulls; bogs which could swallow up the unwary traveler--and his wagon; caves full of Stygian shadow; and, weirdest of all, exposed veins of lignite glowing with the heat of underground fires, lit thousands of years ago by stray bolts of lightning. The smoke seeping out of these veins hung wraithlike in the air, adding a final touch of ghostliness to the scene. Roosevelt could understand why the superstitious Sioux called such territory _Mako Shika_, "land bad."

He loved it there. It was “masculine country,” where “the romance of my life began.” (p. 200) The buffalo hunting did not go well – 5 days of hunting fruitlessly in the rain, but TR kept grinning the whole time. On the sixth day, he finally saw a bison, shot it, then tracked it until it died (p. 212).

Alice

Feb 13, 1884 - Alice gave birth to a baby girl (“Baby Lee”). But she and TR’s mother were both doing poorly, and a follow-up telegram from Corinne (TR’s sister) said, “There is a curse on this house. Mother is dying, and Alice is dying too.”

Alice and TR’s mother both died on Valentine’s Day, 1884. Mittie died at 3am, Alice at 2pm. TR’s diary for the day was a large cross and the words, “A light has gone out of my life.”

With a few brief exceptions, TR never mentioned Alice again in his life.

Morris compares Alice to the character of Dora from David Copperfield. From p. 219,

However cloying his love-talk, however reminiscent his attitude of David Copperfield's to the "child-wife" Dora, Alice Lee was still, after three years and three months of marriage, his "heart's dearest."

I thought this was an apt comparison, although it bugs me a little that the author seems to disdain her for having a character not up to that of her husband. Chapter 9 ends (p. 233) with his thoughts about her:

- Not much more is known about her than the few facts in this biography. She was twenty-two when she died.

- The Roosevelts had initially thought her “attractive but without great depth.” Morris says, “She seemed too simple for such a complex person as Theodore.”

- After her death, the Roosevelts said she was more complex beneath the surface, but Morris considers that sentimental thinking.

Only one woman ventured to suggest, many years later, that Alice, had she lived, would have driven Roosevelt to suicide from sheer boredom. The bitterness of this remark is understandable, since it was made by Alice's successor; but one suspects there may be a grain of truth in it. Alice does seem to have been rather too much the classic Victorian "child-wife," a creature so bland and uncomplicated as to be incapable of spiritual growth.

After her death, he pressed on with the building of Leeholm, the house they had planned together. He wrote to a friend, “I have never believed it did any good to flinch or yield for any blow. Nor does it lighten the pain to cease from working… Indeed I think I should go mad if I were not employed.” He was hyperactive as an assemblyman even while deeply in grief. Page 232 tells us there is no record of TR mentioning Alice again after her death. He was also reticent around “Baby Lee,” who looked so much like her mother.

Chapter 11

He was very active after Alice’s death. His diary is came “a monotonous record of things slain” (p. 278) – grouse, chickens, fauns, elk, grizzlies. He started a ranch in the badlands but traveled repeatedly back and forth to NY to remain active politically.

March 9, 1884 - Less than three weeks after burying Alice, TR goes back to Dakota with Bill Sewall and Willmot Dow, his hunting guides from Maine. He was going into the cattle business out there and wanted their help (in exchange for a portion of the profits, and TR’s willingness to absorb any losses). “There were minor hinderences, such as mortgages and protesting wives,” but they worked it out (p. 269). He brought in 1,000 cattle from Minnesota that summer (p. 273). He named his ranch Elkhorn, having found the skulls of two elk with interlocked antlers and concluding they had fought to the death there.

At one point (p. 281), a guy named Paddock “had stopped by the ranch-site accompanied by several drunken gunmen.” TR wasn’t there, so they ate some of his food and rode off. “Since then, however, Paddock had begun to declare that the Elkhorn shack was rightfully his. If ‘Four Eyes’ wished to buy it, he must pay for it in dollars–or in blood.” So TR rode over to Paddock’s house and knocked on the door. “I understand that you have threatened to kill me on sight,” he said. “I have come over to see when you want to begin the killing.” Paddock was caught off-guard and backpedaled, and there was no more trouble from him.

He made stump speeches for James G. Blaine, a man he despised, when Blaine ran against Grover Cleeveland for president. Cleeveland had just been found to have an illigitimate son, but as Blaine was seen (probably wrongly) to oppose alcohol and Catholicism (p. 284), Cleeveland won.

Chapter 12

TR wrote Hunting Trips of a Ranchman in about 2 months in early 1885. From p. 291,

It was printed on quarto-size sheets of thick, creamy, hand-woven paper, with two-and-a-half-inch margins and sumptuous engravings. Bound in gray, gold-lettered canvas, it retailed at the then unheard-of price of $15, and quickly became a collector's item.

It shows above all his love of all living things. “How such a lover of animals could kill so many of them is perhaps an unanswerable question.” (He had killed literally thousands at this point!)

Sick with cholera morbus, he went to Dakota in April. While trying to cross the Little Missouri River by walking his horse Manitou across a slippery, submerged dam, he and the horse fell in the icy water. TR swam “beside Manitou, pushing ice-blocks out of the horse’s way and splashing water in his face to guide him.” A few days later, he did it again on purpose, this time alone, without any spectators to help him if he got in trouble.

It’s amazing to me how, over and over, living the rough life out in Dakota actually makes him healthier. He benefits more from exertion than from rest.

Leeholm was completed, and he decided to rename it Sagamore Hill. Eleanor Roosevelt, his brother’s daughter, lived just through the trees.

The family motto was carved over the door: Qui plantavit curabit – he who has planted will preserve. (p. 299)

pp. 304-5 give TR’s attitude toward Indians, along with an account of an encounter he had with 5 Indians while riding through the plains alone.

Back in New York, he finally ran into Edith Carow, whom he had been avoiding since Alice’s death. Seeing her now, he found that she was “alarmingly attractive, as he had feared.” They were engaged in November, 1885 but kept it a secret because it would appear to be too hasty; Alice had died just over a year earlier.

Chapter 13

Whereas Alice Lee had evoked “rhapsodies of self-revelation,” Edith appears in TR’s diaries as “E,” and all references are cryptic. Edith “disapproved of excess in language, behavior, clothes, food, or drink,” anyway. And “the mature Roosevelt wrote nothing that he could not entrust to posterity.”

He began writing the book Thomas Hart Benton (about the Senator and Western expansionist).

In March 1886, he went to Elkhorn Ranch. Freak arctic weather hit, and then a gunman and horse-thief called “Redhead” Finnegan stole his boat. The boat was only worth about $30, but TR was a deputy sheriff, “and bound (at least by his own stern moral code) to pursue any lawbreakers.”

While Sewall and Dow prepared a raft for their pursuit, “Roosevelt, ever the schismatic, began to write Thomas Hart Benton.” When they embarked on the raft down the icy river, he brought along the poet Matthew Arnold (a name I recognize, by the way, from the T. S. Eliot book For Lancelot Andrewes, the essay on F. H. Bradley) as well as Anna Karenina. (p. 319)

After a harrowing ride down the river, they eventually catch up and take Finnegan and his two associates by surprise. (p. 322) In this situation, 150 miles from the next big town, with three desperate and violent prisoners, no one would have blamed him had he simply shot them and taken his boat back. “But Roosevelt’s ethics would not allow that.” They poled downriver for 8 days, eventually handing the prisoners over to a rancher who agreed to deliver them to the sheriff in Dickinson. Of the trip, TR said, “There is very little amusement in combining the functions of a sheriff with those of an Arctic explorer.”

Still, between spells of guard duty, he read Anna Karenina. “Tolstoy is a great writer,” he wrote to his sister Corinne. “Do you notice how he never comments on the actions of his personages? He relates what they thought or did without any remark whatever as to whether it was good or bad… a fact which tends to give his work an unmoral tone.” (The Bible, hardly an “unmoral” book, is like this, too – unless the Bible itself was not moral enough for Victorian sensibilities?)

From p. 326, a description of the first election held in Billings County (now in N. Dakota). Its first edict included a promise “to hang, burn, or drown any man that will ask for public improvements at the expense of the County.” (Morris calls these “sound Republican sentiments.”)

He completed Benton in June, having started at the end of March and taken a month off for other duties. It didn’t sell well and is generally “dismissed as historical hackwork” today, but it does reveal some things about TR’s developing philosophy.

Seeing that he his cattle business was hemorrhaging money, he closed up Elkhorn. Sewell and Dow returned to Maine.

Chapter 14

In October 1886, TR reluctantly agreed to let the Republican party nominate him for the next Mayor of New York City. It was a three-way race, with the Democrat Hewitt and a Labor candidate named Henry George. On the day of the election, early returns indicated that Roosevelt was doing poorly and George was doing well. The Republican party bosses responded with a secret message that Republicans must vote for Hewitt, the Democrat – they had to be sure George didn’t win!

TR and Bamie (his sister) left on a ship for England. On board, he met Cecil Spring Rice, who became his best man and long-time friend. TR and Edith were married December 2, 1886 at St. George’s in Hannover Square, London.

Interlude

Winter of 1886-7, a terrible blizzard struck the Badlands. “In the wake of the cowboys trundled a ghoulish convoy of wagons, not seen in the Badlands since the buffalo massacre of 1883. The wagons were driven by bone pickers in the employ of fertilizer companies. For such men alone the winter had brought wealth.”

(I remember bone pickers from Blood Meridian, by Cormac McCarthy. In that book, the connection to a fertilizer company is not explained – an old man collects bones, and the narrator never finds out why, I think.)

Part 2: 1887-1901

Chapter 15

After 15 weeks in Europe, TR and Edith return to NY. Edith was by now pregnant. TR’s sister Bamie had been caring for baby Lee, but Edith insisted that this now end.

TR’s cattle business in the Badlands was in terrible financial straits following the blizzard. “Although his Dakota venture had impoverished him, he was nevertheless rich in nonmonetary dividends. He had gone West sickly, foppish, and racked with personal despair; during his time there he had built a massive body, repaired his soul, and learned to live on equal terms with me poorer and rougher than himself.” (p. 377)

His next literary work was Gouverneur Morris. Gouverneur is the man’s first name (he is not a governor, as I thought!). He is, in fact, one of the founding fathers and the author of the Preamble to the United States Constitution! From page 383, “With his powdered wig and peg-leg, his coruscating wit and picaresque adventures, Morris was a biographer’s dream.”

He submitted the manuscript on Sept. 4. Edith gave birth to a baby boy (Theodore, Jr) on the 13th. (Hey, that’s Roald Dahl’s birthday, too!)

Returning from a hunting trip in Dakota in December and seeing how denuded the land was after being hunted and trapped so much, he formed The Boone & Crockett Club – the first natural preservation society in the US (and possibly in any country). They brought about the National Zoo in Washington as well as legislation that “saved Yellowstone from ecological destruction” (p. 389).

In 1888, he began working on a multi-volume work called The Winning of the West. Needing money, he wrote other books and articles frequently during this time.

At the end of 1889, President Harrison appointed TR as Civil Service Commissioner, and he accepted.

Chapter 16

Although junior to his fellow commissioners, TR naturally became their leader, even after Charles Lyman was elected president of the commission. TR said Lyman was “the most intolerably slow of all men who ever adored red tape.” (p. 404)

Civil Service Reform at this time was like a crusade. The goal of the reformers was for government jobs to be based on merit, not handed out for political favors. TR approached this with his usual exuberance:

Staff and visitors alike were dazed by his energy, exuberance, and ruthless outmaneuvering. "He is a wonderful man," said one caller. "When I went to see him, he got up, shook hands with me, and said, 'So glad to see you. Delighted. Good day, sir, good day.' Then he ushered me to the door. I wonder what I wanted to see him about."

A minor scandal: In investigating corruption, TR promised a job to a witness (Shidy), who turned out to be involved in the corruption, so for TR to keep his promise to Shidy, he had to give him a job that was not based on his merits. He muddled through this.

Page 417 has his encounter with a grizzly bear in Montana, in which it charged at him, taking shot after shot, and finally falling dead at his feet!

The Winning of the West received mostly very good reviews. TR’s favorite review was a negative one, written by historian James Gilmore under a pseudonym, which claimed that TR could not have written the work alone! TR wrote a long and humiliating response, identifying the reviewer by name. “Roosevelt annhiliated him in a letter too long and too scholarly to quote here – unfortunately, for it is a classic example of that perilous literary genre, the Author’s Reply.” (p. 419)

He joined a social circle that included Henry Adams (historian descended from John Adams) and Thomas Reed (witty Speaker of the House). He was a junion member of this group, but they liked him for his vitality and energy. “Men of essentially cold blood, like Reed and Adams and Lodge, grew dependent upon his warmth, as lizards crave the sun.” (What an image! This is a good example of what makes Morris a great writer as well as historian.)

Re: TR’s morals, on page 430, “Many times, as he grew older and more set in his ways, he would protest the moral rightness of his decisions; justice was justice ‘because I did it.’”

On p. 436, when Pres. Benjamin Harrison wants nothing more to do with civil service reform, TR calls him, “a narrow-minded, prejudiced, obstinate, timid old psalm-singing Indianapolis politician.” Singing the psalms should not imply timidity! Christ sang them, and so do I!

Chapter 17

TR’s younger brother, Elliott, was declining into drunkenness. In 1890, he, his wife Anna, and their 6 month old child departed for Europe, planning not to touch alcohol while on vacation. He relapsed, Anna was pregnant again (“and was afraid of spending the winter alone with her unstable husband”), and they sent for Bamie to come help. Meanwhile, one of Elliott’s servants, Katy Mann, claimed to be pregnant with his child.

He published a history of New York City that received decent, though not glowing, reviews. After some weeks spent engaged in Washington social life, “his Dutch Reformed conscience began to bother him. ‘I have been going out too much… I wish I had more chance to work at my books… I don’t feel as if I were working to lasting effect.’” (447)

A familiar sentiment! But what lasting effect can anyone work to? 130 years later, who reads TR’s books? Some still do – they had as much of a lasting effect as one could hope for –, but for how much longer? In my own work, I write software that might still be running in 5-10 years, maybe 20 or more for a really successful product. But more likely, it’s destined to die an unceremonious death sooner than that. You can’t take it with you, and you can’t leave yourself behind; you can only know the Lord and serve your neighbor. Ephemeral acts of faith, love, and charity are “working to lasting effect,” while solid objects of stone or words written for posterity are fleeting.

Katy Mann had the baby and was demanding $10,000! “It was impossible to deny Elliott’s culpability: an ’expert in likenesses’ had seen the baby, and its features were unmistakably Rooseveltian.” (451 – an unusual occupation, but it’s not like they could do a DNA test) Eventually, she just fades from the story, though – apparently, she did get paid some amount, but the details are lost. Elliott ended up turning himself in to an asylum, and Anna died (diptheria).

Lots of details in this chapter about civil service reform, TR fighting with Postmaster General John Wanamaker about the spoils system in Baltimore.

Chapter 18

The Winning of the West is about “the remorseless advance of Anglo-Saxon civilization” and specifically about the white settlement of Indian lands west of the Allegheny River. He writes (477), “The most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages, though it is apt to appear the most terrible and inhuman. The rude, fierce settler who drove the savage from the land lays all civilized mankind under a debt to him.” This reminds me of Gus and Call in Lonesome Dove, who helped run the Indians out of Texas but were unappreciated a few years later.

Much of what he says sounds racist to modern ears, but “any black or red man who could win admission to ’the fellowship of the doers’ was superior to the white man who failed.” So it seems like TR’s good opinion is ultimately based on merit, not race. (On pp. 482-3 I noted a passage that seems racist, followed by one that doesn’t. It may be complicated.)

Feb. 1895: Cuba declared war against Spain.

Apr. 1895: TR accepted the post of New York Police Commissioner.

Chapter 19

June 1895: TR begins walking the streets of NYC at night to see whether officers are doing their jobs. “It became apparent that New York’s Finest were also among its rarest.” (508) He popped up incognito and began dressing down policement who were not at their posts. He likewise praised those who were patroling well. He brought press with him in some cases.

“One interprising peddler showed up on Mulberry Street with a sackful of celluloid dentures” which whistled through TR’s trademark grin, and he quickly sold out of them. (511)

The Sunday Excise Law forbade selling liquor on Sunday. This was completely unenforced. TR did not really agree with the law, but as Police Commissioner he felt he must uphold the law, even though this made him unpopular. “I do not deal with public sentiment. I deal with the law.” “Roosevelt argued that the honest enforcement of an unpopular law was the most effective way to bring about its repeal.” (520)

After meeting TR, Bram Stoker (author of Dracula) wrote, “Must be President some day. A man you can’t cajole, can’t frighten, can’t buy.”

Chapter 20

Lots of struggle between TR and Andrew Parker, fellow member of the Police Board. Parker would not show up for meetings, making it impossible to hold a vote on certain issues that required unanimous agreement. TR can’t get anything done.

Chapter 21

1896: TR campaigned for William KcKinley and against William Jennings Bryan, who opposed the gold standard. Although McKinley feared TR would be too eager for war, he eventually appointed him Assistant Secretary of the Navy (on April 6, 1897 – p. 583), after significant cajoling from Henry Cabot Lodge and Mrs. Belamy Storer.

Chapter 22

John D. Long was Secretary of the Navy, so TR reported to him, at least officially. Long was “indolent,” the opposite of Roosevelt.

For the “first great speech of his career,” TR chose a theme from George Washington: “To be prepared for war is the most effectual means to promote peace.” (593) He wanted to quickly build up the American Navy.

He dismissed the suggestion that such a program would tempt the United States into unnecessary war... "All the great masterful races have been fighting races; and the minute that a race loses the hard fighting virtues, then... it has lost its proud right to stand as equal to the best." (594)

There are higher things in this life than the soft and easy enjoyment of material comfort. It is through strife, or the readiness for strife, that a nation must win greatness.

[I find this inspiring; it makes me want to be better prepared for difficulties.]

TR and Long did not see eye-to-eye on this. Around p. 600, Long goes on vacation, and TR (as “acting Secretary”) begins signing things, issuing orders for reducing paperwork, etc. He wrote “soothingly” to Long to keep him away on vacation. Some of his speeches upset Long, but his vacations were more important, so TR got another period as acting Secretary in August.

He now entered upon one of those periods of near-incredible industry which always characterized his assumption of new responsibilities -- whether it be the management of a ranch, the researching of a book, or, as in this case, the administration of the most difficult department in the United States Government. (606 -- there follows a long list of his activities during just 22 days of official duty)

The Boston Globe wrote of him, “It would never do to permit such a man to get into the Presidency. He would produce national insomnia.” (616)

Chapter 23

January 1898: Following a riot in Cuba, TR was eager to see the US Navy bolster its forces and prepare for war, should it come to that. Ships should redeploy to more strategic locations – they would take weeks to reach useful positions, so he wanted to begin that now, before anything started. (621)

A ship called the Maine was sent to Havana. Sometime on the night of Jan. 15, it was blown up and destroyed. This was widely believed to be an accidental explosion. Weeks of excitement and attempts to figure out the truth left Long exhausted, and on Feb. 25, he took a half day off, leaving TR in charge.

During his 3-4 hours as acting Secretary, TR sent a cablegram redeploying ships to Hong Kong to be prepared to block Spanish ships deployed along the Asiatic coast. He sent similar instructions all over, always reminding the ships to “keep full of coal.” He authorized the Navy’s coal buyers to purchase the maximum amount to keep in stock. He requisitioned guns and ordered ammunition. He demanded that Congress authorize recruiting an unlimited number of seamen. In a single afternoon, he “placed the Navy in a state of such readiness as it had not known since the Civil War.”

When Long returned the next day, he “resolved never to leave Roosevelt in solo charge of the department again.” He thought that TR was overcome by nerves due to some personal issues (Edith was sick, e.g.).

Long did not understand that extreme crisis, whether of an intimate or public nature, had precisely the reverse effect on TR. The man's personality was cyclonic, in that he tended to become unstable in times of low pressure... History has shown that his behavior as Acting Secretary of the Navy on 25 February 1898, was neither nervous nor spontaneous. It was the logical result of ten months of strategic planning.

TR never waited to prepare for trouble. The amount of prep may help explain how he remained so calm and in control under pressure.

An interesting negotiation for a ship on p. 633. Rather than give all the specifications for the ship’s condition, TR simply wrote into the contract that the ship must be “delivered under her own steam at a specific point and within a specific period. In one sentence, he thus covered all that might have been set forth in pages and pages of specifications. For the vessel had to be in first-class condition to make the time scheduled in the contract!”

In March, McKinley learned that the Maine had in fact been blown up by a Spanish submarine mine. Congress finally resolved to fight for Cuban independence on April 19, 1898, one year to the day since TR took office.

For months (years! As far back as 1886, according to p. 642), TR had said he would join the fight if America went to war. But now imagine the pressure tempting him to reverse this. “Nearly every newspaper in the country urged Roosevelt to stay on in the Navy Department, where his services were now needed more than ever.” One writer said that “his departure was the cowardly act of a brave man.” And it seemed that his friends had never fully believed he’d follow through, either. “It was therefore vital that he prove himself, once and for all, a man of his word. If he backed down now, what of any future promises he might make to the American people?” (641) It would be VERY easy to cave in to this kind of pressure.

TR became a Lt. Colonel under Col. Leonard Wood. They were quickly flooded with applications from men wishing to fight. (643)

“In seven hours of stately maneuvers off Manila, George Dewey had destroyed Spain’s Asiatic Squadron. Almost every enemy ship was sunk, deserted, or in flames; not one American life had been lost, in contrast to 381 Spanish casualties.” TR’s preparations put him in position to be very effective when the time came.

Chapter 24

Into the Rough Riders (aka the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry), TR enlisted 50 men from “Ivy League schools and the better clubs of Manhattan and Boston,” along with over a thousand rough volunteers. They assembled near San Antonio to train.

A small note: When traveling, TR “punished all cases of drunkenness severely, ‘in order to give full liberty to those who would not abuse it.’” (653) I like that way of thinking.

[While all riding in a train to Florida] As he waved at grizzled old Southerners, and they in turn waved the Stars and Stripes back at him, Roosevelt reflected that only thirty-three years before these men had been enemies of the Union. It took war to heal the scars of war; attack upon a foreign power to bring unity at home. But what future war would heal the scars of this one? (654)

Leading them all was Brigadier General William Rufus Shafter. Shafter weighed 300 pounds and could barely move himself up a stairway. As TR later put it, “Not since the campaign of Crassus against the Parthians has there been so criminally incompetent a General as Shafter.” (655) There were all kinds of problems getting the men and their horses onto boats, but with some quick initiative (658), they finally left from Tampa aboard the Yucatan on June 14, 1898.

Chapter 25

“Aboard the Yucatan a macabre toast was drunk: ‘To the Officers – may they get killed, wounded, or promoted!’” (665)

While debarking, they had trouble getting the horses ashore, so Shafter had the horses “shoved into the sea and left to find the beach for themselves.” Some started swimming in the wrong direction, but a bugler on the beach blew a cavalry call, and they turned back. (667) One of TR’s horses (named Rain-in-the-Face) was accidentally drowned, but his other horse, Texas, made it to shore.

Another great example of TR’s preparedness: After dropping off its other passengers, the Yucatan “steamed away, taking large quantities of personal effects with her before any attempt was made to unload them. Roosevelt was left standing on the sand with nothing but a yellow mackintosh and a toothbrush. Fortunately, his most essential items of baggage were inside his Rough Rider hat: several extra pairs of spectacles, sewn into the lining. If he had to meet his fate in Cuba, he wished to see it in clear focus.” (667)

On the seven-mile hike to Siboney, he refused to ride Texas “while my men are walking.” He walked and sweated like the rest of them, “earning the affectionate respect of his troopers.” (669)

From p. 672: Stephen Crane, journalist and author of The Red Badge of Courage, followed Roosevelt to report on his exploits, though TR did not like him.

Signaling each other with bird calls in the jungle, the Spaniards ambushed the Americans in The Battle of Las Guasimas. TR handled it well.

I love this story of government beaurocracy:

On the morning of 26 June, Roosevelt got wind of a stockpile of beans on the beach, and marched a squad of men hastily down to investigate. There were, indeed, eleven hundred pounds of beans available, so he went into the commissary and demanded the full amount for his regiment. The commisar reached for a book of regulations and showed him that "under sub-section B of section C of article 4, or something like that," beans were available only to officers. Roosevelt had learned enough during his six years as Civil Service Commissioner not to protest this attitude. He merely went outside for a moment, then returned and demanded eleven hundred pounds of beans "for the officer's mess."

Commisar But your officers cannot eat eleven hundred pounds of beans. Roosevelt You don't know what appetites my officers have. Commisar (wavering) I'll have to send the requisition to Washington. Roosevelt All right, only give me the beans. Commisar I'm afraid they'll take it out of your salary. Roosevelt That will be all right, only give me the beans. So the Rough Riders got their beans, and the requisition went to Washington. "Oh! what a feast we had, and how we enjoyed it!"

TR became a Colonel (680) on the battlefield after two Generals died from fever.

This story reminds me of Nebuchadnezzar:

At some point (685), waiting for orders to advance, they were lying low, with men occasionally being picked off by Spanish Mauser rifles. Even TR was lying low, “but Bucky O’Neill insisted on strolling uo and down in front of his troop, smoking his perpetual cigarette, as if he was still walking along the sidewalk in Prescott, Arkansas. ‘Sergeant,’ he said to a protestor, ’the Spanish bullet isn’t made that will kill me.’ He had hardly exhaled a laughing cloud of smoke before a Mauser shot went z-z-z-z-eu into his mouth, and burst out the back of his head.” He was dead before he hit the ground.

The story about the sharks (690) is typical of TR. He and a lieutenant, Greenway, swam out to look at the wreck of the Merrimac. Swimming out and back, they were accompanied by sharks, which did not perturb Roosevelt at all.

The end result of all this on TR was “purgation. Bellicose poisons had been breeding in him since infancy… But at last he had had his bloodletting… Theodore Roosevelt was at last, incongruously but wholeheartedly, a man of peace.”

Chapter 26

Following his triumphant return from Cuba, TR was nominated and won as Governor of New York. He was now 40 years old.

Chapter 27

When people wanted to nominate him for Vice Pres., TR said he “should like a position with more work in it.”

On p. 742, one of my favorite scenes: he takes a vacation and declares to his sister Corinne that, “I don’t mean to do one single thing that month except write a life of Oliver Cromwell.”

According to his stenographer, William Loeb, the Governor would appear in his study every morning with a pad of notes and a reference book or two, and proceed to talk "with hardly a pause," pouring out dates and place-names as copiously as any college professor. [One houseguest] remembered him calling in another stenographer and dictating gubernatorial correspondence in between paragraphs of Cromwell, while a barbet tried simultaneously to shave him.

Switching back and forth between two stenographers while being shaved – that’s TR’s idea of a vacation!

He was, somewhat against his wishes, nominated for VP along with McKinley for President. TR cast the only vote against himself.

Epilogue - September 1901

His time as VP began formally on March 4, 1901. On Friday, Sept. 6, McKinley was shot by an anarchist named Leon Czolgosz. Learning that McKinley’s condition was improving, TR took a short trip into the Adirondacks with his family on the 10th, which was reassuring news to the American people.

The book ends with a messenger approaching him in this remote location, carrying news of the President’s death.

Some other entertaining details

Page 254 has this description of James G. Blaine: “The mere sight of his boozy, silver-bearded features in a train window is enough to make women weep with adoration, and men vow to God that they will never vote for any other Republican.”

Responding to TR’s self-righteousness, Thomas Reed said, “If there is one thing for which I admire you, it is your original discovery of the Ten Commandments.” (601)

When Pres. McKinley delayed declaring war on Spain in Cuba, TR said, “McKinley has no more backbone than a chocolate eclair.” (638)

[While speaker of the NY Assembly,] he was never bored, and found entertainment in the dullest moments of parliamentary debate. With a writer's eye and ear, he noted down incidents and scraps of Irish dialogue for future publication. There was Assemblyman Bogan, who **"looked like a serious, elderly frot,"** standing up to object to the rules, and, on being informed that there were no rules to object to, moving "that they be amended until there are-r-e!" (p. 227)

[After breaking his arm during a fox hunt], he wrote to Lodge: "I don't grudge the broken arm a bit... I'm always ready to pay the piper when I've had a good dance; and every now and then I like to drink the wine of life with brandy in it." (p. 311)

Vocab

- sutler (9) – a civilian merchant who sells provisions to an army in the field or in camp

- I cry peccavi (412) – an exclamation of guilt

- The Winning of the West had been published during his absence, to panegyrical newspaper reviews. (412) – speech or text in praise of something

- Although he complained about being treated like “a corpulent valetudinarian,” it was plain that he was physically and emotionally spent. (456) – a person unduly concerned about their health

- TR’s NYC Police Commissionership had been “one long elegant shindy” (586) – a noisy quarrel or a large, lively party

- John D. Long was indolent (590) – lazy, avoiding exertion

- The less work Long wanted to do, the more power TR could arrogate to himself. (591) – to take without justification

- bellicose (597) – aggressive, ready to fight

- vulpine (686) – relating to foxes, crafty.